Irritable bowel syndrome disrupts the normal functioning of the digestive tract. The typical symptoms are diarrhea, constipation and abdominal pain. The classic course of treatment is mainly focused on relieving the symptoms. However, micronutrient medicine uses a range of substances to tackle the underlying cause of the condition. Find our here what these are.

Causes and Symptoms

The causes of irritable bowel syndrome

Irritable bowel syndrome, IBS for short, is a functional disorder of the digestive tract. The condition causes non-specific abdominal symptoms such as pain. The exact cause of IBS is unclear. Doctors suspects that the combination of several different factors causes the development of irritable bowel syndrome:

Genetic Predisposition: Some people have a genetic predisposition to developing irritable bowel syndrome. Women are more commonly affected than men. The reasons for this are still unknown.

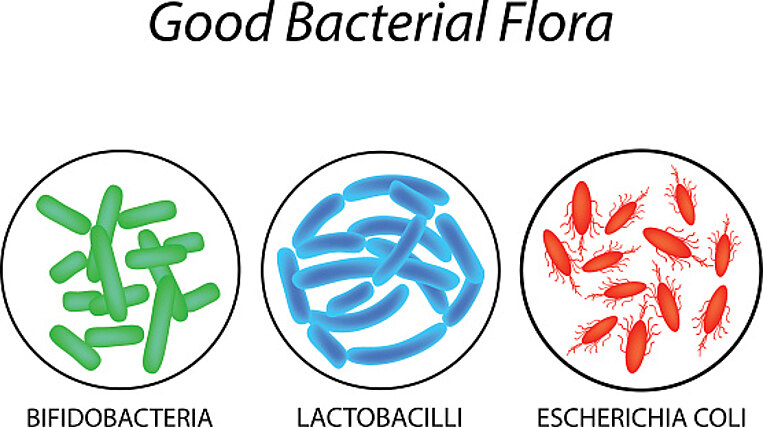

Changes to the intestinal flora: People with irritable bowel syndrome show changes in the composition of their intestinal flora. This means a high number of undesirable intestinal bacteria, inflammatory processes, immune system disorders, and a negatively affected intestinal wall.

Leaky Gut Syndrome (Disruption of the intestinal barrier): Those affected often have a more permeable intestinal wall. When the barrier function of the intestinal wall is weakened it is easier for harmful substances to enter the tissue and bloodstream. This can cause irritation, discomfort, and inflammation.

Hypersensitivity of the intestinal nervous system: The movement of the intestinal tract is controlled by a complex nervous system. These natural intestinal movements are disrupted in people with irritable bowel syndrome. Their intestinal tract reacts rapidly, causing a painful sensation of fullness, like a build-up of air which stretches the intestinal tract.

Activation of the immune system: In some sufferers, the cause of irritable bowel syndrome lies in activation of the immune system. There is an increased production of certain types of chemical messenger substances (for example, histamine). This causes persistent inflammation. Inflammation triggers painful reactions in the body.

Inflammation: Intestinal inflammationtriggered by viruses or bacteria can lead to irritable bowel syndrome and can persist for weeks or even months.

Stress: Irritable bowel syndrome is not a disease which has an underlying psychological cause. However, there is evidence that the nervous system of the internal organs is highly sensitive in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Psychological stress, anger, or tension can trigger the symptoms or make existing symptoms worse.

The symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome

The typical symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome are abdominal pain, abdominal cramps, and a sensation of pressure or fullness in the lower abdomen. Abdominal bloating and flatulence are also common. There are also change to bowel movements when suffering from irritable bowel syndrome: Both chronic diarrhea (diarrhea type) and constipation (constipation type) can develop as a result of the disease - or alternating between the two.

According to existing guidelines, the presence of irritable bowel syndrome is confirmed when two of the following criteria are met:

- The symptoms are chronic and last longer than three months.

- Symptoms such as abdominal pain and flatulence originating in the intestines and a change in bowel movements.

- It can be ruled out that other diseases are the cause of the symptoms, such as: chronic-inflammatory intestinal disease, gastrointestinal infection, gastritis, tumours or food intolerances, e.g., gluten [celiac disease], lactose or fructose.

Irritable bowel syndrome is not contagious. Normally, irritable bowel syndrome is a chronic condition; this means the symptoms are long-term.

Statistical surveys have shown those suffering from irritable bowel syndrome are also more likely to suffer from anxiety disorders, depression and other negative emotions.

Aim of the treatment

What is the standard treatment for irritable bowel syndrome?

Irritable bowel syndrome is an exclusion diagnosis. This means that the doctor must first rule out other possible more serious diseases. If all examinations show no pathological findings, the doctor will diagnose IBS. The course of treatment is mainly focused on relieving the symptoms.

Due to the fact that irritable bowel syndrome does not have one identifiable cause, there is no uniform course of treatment. Instead each individual case must be evaluated to determine which symptoms can be treated and which triggers can be avoided.

Treating irritable bowel syndrome with medication:

- Antispasmodic medication is used (e.g., Buscopan®) for the pain management of cramps.

- Medication containing the active substance loperamide (Imodium®, Lopedium®) treat the diarrhea.

- Laxatives containing the active substance bisacodyl (Ducolax®, Muxol®) help to treat the constipation. The treatment of symptoms such as diarrhea or constipation will also relieve symptoms such as flatulence and feeling full.

- Depending on thepsychological symptomsand pain levels, in accordance with existing guidelines, antidepressants can also be prescribed, for example, tricyclic antidepressants (such as Elavil (Endep®, Vanatripl®), Doxepine (Aponal®) or Trimipramine (Surmontill®, Herphonal®) or Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors like Paroxetine (Paxil®, Seroxat®) or Fluoxetine (Prozac®, Sarafem®).

Diet and Psychotherapy:

The role that diet plays is being discussed.

There are no definitive dietary recommendations. However, there is evidence that changes to an individual’s diet can lead to an overall improvement in symptoms, for example, by avoiding short-chain sugars (carbohydrates) which trigger fermentation processes in the intestinal tract.

Info

A treatment approach for irritative bowel syndrome is the low FODMAP diet. This approach focuses on removing foods from the diet that contain carbohydrates which are easily broken down by bacteria (oligosaccharides, disaccharides and monosaccharides) This includes fructose from apples, pears, honey, onions, lactose from milk, or artificial sweeteners with sorbitol.

There are studies which have shown that an accompanying course of psychotherapy can be beneficial, for example, hypnosis focusing on the digestive tract or cognitive behavioral therapy.

The aims of micronutrient medicine

Micronutrient medicine uses vitamins, minerals and other supplements to reduce the symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome and improve the patient's overall well-being.

- Probiotics help return the intestinal flora to a natural balanced state and promote intestinal wall health.

- Dietary fibers help promote probiotic bacteria.

- Vitamin D helps regulate the immune system.

- Omega-3 fatty acid supplements help stop intestinal wall inflammation.

- B vitamins enable the intestinal mucous membrane to regenerate.

Treatment using micronutrients

Probiotics for healthy intestinal flora

How probiotics work in the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome

Disruption of the intestinal flora is most likely an important risk factor for irritable bowel syndrome. Probiotics contain many "good" microorganisms which colonize the intestinal tract and deprive organisms that cause illnesses of their food source. This stops these pathogens (bacteria which cause illnesses) from multiplying. Probiotic microorganisms also enhance the body's immune responses and help in the production of antibodies. Probiotics strengthen the barrier function of the intestines and make it more difficult for bacteria to enter the body.

Several extensive studies have shown that probiotics can relieve the symptoms of IBS. An overview study found that a positive effect of probiotics on the symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome was recorded in 34 of 42 studies.

Several professional medical associations also recommend the use of probiotics to treat irritable bowel syndrome. The type of probiotic depends of the symptoms of the IBS. Several of the available studies point to the fact that in the treatment of some symptoms, certain individual types of bacteria are a more effective supplement than a combination supplement:

- For constipation, bacteria from the Escherichia coli Nissle strain, Bifidobacterium animalis or Lactobacillus casei Shirota are recommended.

- Flatulence coupled with painwere effectively treated using Bifidobacterium infantis, Bifidobacterium animalis ssp. lactis, Lactobacillus casei Shirota and Lactobacillus plantarum.

- Fordiarrhea combinations of Lactobacilli, Bifidobacteria, and the yeast type Saccharomyces boulardii are preliminary recommended.

Conclusion:

Research is attempting to tailor the combination of supplements to symptoms in each case. This approach has not yet been fully successful. The symptoms often alternate, for example, between diarrhea and constipation. Therefore, it is worthwhile trying different combinations. Combination supplements are worth an attempt in the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome.

Probiotic dosage and intake recommendations to treat irritable bowel syndrome

Probiotics are available in powdered, tablet, or capsule form. They should be taken at mealtimes with plenty of water: Both of these methods ensure that the probiotics reach the digestive tract alive despite being exposed to the digestive acids in the stomach. It is important that probiotics are taken over a long period of time to ensure they are fully effective. Then when the intake of useful bacteria stops, the existing one will be slowly expelled by the body.

A sufficient amount of good bacteria must be taken to help relieve the symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome. According to existing studies, a dosage of above ten billion is effective. On the supplement packaging, this amount will be displayed as 109 or 1010 Colony Forming Units (CFU).

Tips

High numbers of bacteria are important because a large number of bacteria will be neutralized by the acids in the stomach before reaching the intestinal tract. High-quality probiotic supplements are bred and processed to ensure that they are not damaged by the acids in the stomach (enteric capsules). By the way: The minimum level of probiotic bacteria intake cannot be achieved solely through your diet. This is why it is advisable to use probiotic supplements.

Instructions for a weakened immune system or if taking medication

The seriously ill, those who have recently undergone surgery, very old people, and those with a weakened immune system (for example during chemotherapy) should have a doctor critically evaluate the possible benefits of probiotic therapy.

Probiotics which contain the yeast saccharomyces boulardii should not be used by the seriously ill or those patients with central venous catheters. Additionally, people in close proximity to these groups should avoid this supplement due to the risk of transmission. Infection has previously been observed

If you have been prescribed antibiotics to treat a bacterial intestinal infection, make sure that you do not take the antibiotics at the same time as the probiotic supplements. Leave an interval of between two and three hours between the use of each.

Dietary fibers help promote the positive effects of probiotic bacteria

How dietary fibers work in the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome

Dietary fibers, known as prebiotics, are plant components of foodstuffs which cannot be digested by the body. When they arrive in the large intestine they act as food for the health-promoting intestinal bacteria such as bifidobacteria. This makes it more difficult for harmful bacteria to colonize the intestinal tract.

With one of the major symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome being constipation, a high level of dietary fiber intake is recommended. Extensive studies have shown that irritable bowel patients who take sufficiently high levels of dietary fiber showed an improvement in their symptoms. Dietary fiber is also worth a try for patients who suffer from pain, flatulence, and diarrhea.

However, some studies have shown that increased supplementation with dietary fiber was no more effective than a placebo. It is clearly dependent on the type of dietary fiber used: Soluble, gel-like fibers, such as psyllium husks, were shown to be effective while non-soluble dietary fibers such as wheat bran were shown to be ineffective. Short-chain sugar compounds (insulin, oligofructose), which can lead to an increase in the production of digestive gases which in turn causes digestive problems are also problematic.

Example: Psyllium husks

Psyllium husks are able to bind a lot of water in the digestive tract causing the weight of the stool to increase. This creates a gel-like texture which makes it easier for the stool to slide through the digestive tract.

Soluble dietary fibers have proven to be effective for the treatment of constipation stemming from irritable bowel syndrome. During an initial study, symptoms in the group given 10 grams of psyllium husk a day improved twice as much after twelve weeks compared to the groups given a placebo or wheat bran.

Example: Resistant starch

Resistant starch cannot be broken down in the digestive tract and therefore is able to reach the large intestine. Here the starch is metabolized by bacteria and short-chain fatty acids, such as butyrate, are produced. These fatty acids play an important role in intestinal health: They provide nutrition to the cells of the large intestines, regulate the movement of the intestines and inhibit the growth of the bacteria which cause illnesses (pathogens).

Irritable bowel syndrome is often accompanied not only by weakening, but also constant inflammation of the intestinal mucous membrane which is triggered by a combination of various factors. Tests have shown that butyrate can help counteract these inflammatory tendencies. Taken together with standard anti-cramping medications or medications that stimulate the bowels, butyrate was shown not only to relieve irritable bowel syndrome but also improve overall quality of life. The standard medications by themselves did not deliver a notable improvement.

Dosage and recommended use of dietary fibers:

To reduce the symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome, a dosage of 10 milligrams of psyllium husks or up to 25 grams of resistant starch is recommended. It is also important that you drink enough fluid – at least one glass (200 milliliters) of water each time you take the supplement.

Dietary fibers can cause flatulence, especially if the intestinal tract which is not used to the substance. Therefore, make sure not to begin with the highest dose, instead start with smaller doses and increase over time - the intestinal tract needs a while to adjust to the new diet.

Dietary fiber supplements are not recommended for the treatment of children with abdominal pain and chronic constipation.

Tips

Make sure to choose your type of dietary fiber supplements carefully and pay attention to the correct dosage: Too small a dosage will not have the desired effect. Too large a dosage will cause a buildup of intestinal gases which cause painful flatulence or make existing flatulence worse. In many cases the correct dosage can only be obtained through trial and error.

Not all types of prebiotic supplements are suitable for all types of patients: A study showed that between 36 and 64 percent of those affected also suffered from lactose or fructose intolerance. Certain types of prebiotic supplements are fructose-based, for example fructooligosaccharide (= oligofructose, FOS, or insulin). Fructose belongs to the group of easily digestible simple sugar compounds. The consumption of these types of sugar is avoided during a low FODMAP diet.

Resistant starch can be consumed during a low FODMAP diet without any problems. Resistant starch is comprised of many different carbohydrate units which make it more difficult for the body to break down and are better tolerated by the digestive system.

Vitamins D strengthens the intestinal immune system

How vitamin D works in the treatment of Irritable Bowel Syndrome

Vitamin D plays an important role in the immune system and in the regulation of inflammatory processes as well as in the intestines. Low vitamin D levels may promote the development of inflammatory intestinal diseases, such as Crohn's disease.

Also, there is evidence that low vitamin D levels can influence the development and progression of irritable bowel syndrome. Case-control studies have shown that the vitamin D levels of irritable bowel syndrome patients are often too low. This also applies to children. During case-control-studies two groups are compared to one another: One group (ill) and a control group (healthy).

Irritable bowel syndrome patients who received vitamin D supplements during an initial medical study showed a notable improvement in their quality of life when compared to the group who received a placebo. Further testing showed that low vitamin D levels aggravated symptoms which can develop when suffering from irritable bowel syndrome, such as depression. The study authors pointed out the intake of vitamin D supplements may also help to reduce the severity of these symptoms. However, the available study material is not able to definitively confirm this correlation.

If you suffer from irritable bowel syndrome, it is recommended to have your vitamin D levels tested and then treat any diagnosed deficiency with a suitable supplement.

Vitamin D dosage and intake recommendations to treat irritable bowel syndrome

Ideally, vitamin D dosage is based on vitamin D levels in the blood: To treat a slight deficiency, between 1,000 and 4,000 International Units per day are advisable. To treat more severe deficiencies, a higher dosage prescribed by a doctor may be necessary.

Make sure to always take the supplements at mealtimes. Vitamin D is a fat soluble vitamin and requires fat from your diet to be absorbed by the body.

Laboratory vitamin D level testing

To find out if a patient with irritable bowel syndrome is also suffering from a vitamin D deficiency, the levels of the vitamin D precursor calcidiol (25-OH-Vitamin-D) in the blood serum are determined. Blood serum is the liquid of the blood without blood cells.

A value of below 20 nanograms of calcidol per milliliter is considered insufficient The ideal value is between 40 and 60 calcidol nanograms per milliliter. It is advisable to test vitamin D levels twice a year.

Instructions for reduced kidney function, sarcoidosis, and if taking medication

Thiazide diuretic medications reduce the amount of calcium removed by the body. This means that the calcium remains in the blood. Because vitamin D also increases calcium levels in the blood, vitamin D should only be taken in combination with thiazide diuretics when the calcium levels are regularly monitored. The thiazide class of diuretics includes the active substance hydrochlorothiazide (Esidrix®) Indapamide (e.g., Lozol®) and Xipamide are other types of thiazide medications.

Vitamin D supplement should not be used by patients suffering from reduced kidney function or kidney stones without undergoing regular vitamin D level blood testing. Vitamins D can increase the calcium levels in the blood. The diseased kidney is unable to sufficiently remove the calcium from the blood.

Sarcoidosis patients often have high calcium levels in their blood In these cases, the use of vitamin D supplements is not recommended.

Omega-3 fatty acids effectively combat inflammation.

How omega-3 fatty acids work in the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome

Many irritable bowel sufferers have mild but persistent inflammation of the intestinal mucous membrane. These inflammatory processes disrupt the normal functioning of the intestines and trigger symptoms. Omega-3 fatty acids often help intestine inflammation to subside. These acids are used to create substances which can actively end inflammation. Initial studies have shown that patients with irritable bowel syndrome often have low levels of omega-3 fatty acids, for example, eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA).

Omega-3 fatty acids are not only effective in the treatment of inflammation related to IBS. Preliminary studies have shown that omega-3 fatty acids also triggered positive changes in the make-up of the intestinal flora in patients with IBS.

An initial study carried out on Asian women showed a correlation between low omega-3 levels and a higher rate of depression as an accompanying symptom of irritable bowel syndrome. Omega-3 could also be effective in combating depression-related symptoms.

Overall, the studies with omega-3 are encouraging, but the study authors have pointed out that these results require further confirmation.

Omega-3 fatty acids dosage and intake recommendations to treat irritable bowel syndrome

Between 2,000 and 5,000 milligrams per day of omega-3 fatty acids (EPA and DHA) are recommended for irritable bowel patients.

EPA and DHA are found in oily fish and fish oil dietary supplements. Omega-3 supplements should always be taken at mealtimes: The fat from the food improves the body's ability to absorb the fatty acids in the intestinal tract.

Make sure to purchase high-quality and high-purity supplements. Use only purified fish or krill. Krill is naturally very pure. Paying attention to the quality of the products you purchase ensures that you will reap the full benefit of the valuable fatty acids.

The omega-3 index can be determined by laboratory tests.

A blood test can determine the omega-3 fatty acids in the body (omega-3 index). The test identifies the amount of omega-3 fatty acids contained in the red blood cells. The value should be above four percent but ideally above eight percent. This would mean that high-quality omega-3 fatty acids are present in eight out of every 100 red blood cells.

Instructions if taking anticoagulants (blood thinners) or during illness

Omega-3 fatty acid also has anti-inflammatory properties. This may result in the need for reduced dosages of blood thinning mediations, known as anticoagulants (for example, Marcumar®). If you are taking blood thinning medication or coagulation inhibitors and omega-3 supplements (1,000 milligrams or more), then your blood coagulation values should be tested regularly. Your doctors can then adjust the dosage as required.

Those with blood coagulation disorder should avoid taking omega-3 supplements.

B vitamins reinforce the intestinal mucous membrane.

How B vitamins work in the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome

B vitamins play a major role in the body's energy production and cell division processes. This is particularly important for the intestinal mucous membrane as these cells naturally divide on a regular basis. A sufficient intake of vitamin B ensures that intestinal damage can heal properly.

A B vitamin deficiency has serious consequences for the intestinal mucous membrane:

Vitamin B2 (Riboflavin) not only ensures energy production but also provides antioxidant cell protection. A review of several studies showed that IBS patients did not have a sufficient intake of vitamin B2, along with other compounds, as part of their diet.

Vitamin B6 (Pyridoxine) plays an important role in many metabolic processes. These include the building of cellular proteins. A vitamin B6 deficiency leads to loss of appetite and diarrhea. An initial study showed that the symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome were especially pronounced in those cases where the person's intake of vitamin B6 in their diet was too low.

Vitamin B12 (Cobalamin) is used for cell division and the functioning of the nervous system for example. Vitamin B12 is often present in patients with inflammatory intestinal diseases.

The metabolism of frequently dividing cells also requires vitamin B1, biotin, folic acid, niacin and pantothenic acid.

B vitamin dosage and intake recommendations to treat irritable bowel syndrome

IBS sufferers should ensure that they are taking a sufficient amount of B vitamins. A multi-micronutrient supplement which contains all B vitamins is therefore advisable:

- Vitamin B1: up to 5 milligrams

- Vitamin B2: up to 5 milligrams

- Vitamin B6: up to 10 milligrams

- Vitamin B12: 10 to 20 micrograms

- Folic Acid: 200 to 400 micrograms

- Biotin: 100 to 200 micrograms

- Niacin: 50 milligrams

- Pantothenic acid: 30 milligrams

Tips

Some people possess only a limited ability to metabolize folic acid. The reason for this is a defective enzyme which produces an insufficient amount of the active form of 5-methyltetrahydrofolate from folic acid. Therefore, this group should supplement directly taking the active 5-methyltetrahydrofolate type of folic acid.

Instructions for during pregnancy, when breastfeeding, if suffering from kidney disease or if taking medication

Pregnant women and those who are breastfeeding should only use high-dosage B vitamin supplements if they have been diagnosed with a deficiency. They should also consult their gynaecologist beforehand.

Vitamin B12: Be careful with impaired kidney function

High-dosage B vitamin supplements can cause a deterioration in the function of the kidney in patients with a pre-existing kidney function disorder. Experts believe that this is due to vitamin B12. Hi doses of cyanocobalamin can be harmful in patients with impaired kidney function. To combat this, it is recommended to take vitamin B12 as methylcobalamin.

Dosage overview

Daily micronutrient recommendations for irritable bowel syndrome | |

|---|---|

Vitamins | |

Vitamin B1 | up to 5 milligrams (mg) |

Vitamin B2 | up to 5 milligrams |

Vitamin B6 | up to 10 milligrams |

Vitamin B12 | 10 to 20 micrograms (µg) |

Folic Acid | 200 to 400 micrograms |

Biotin | 100 to 200 micrograms |

Niacin | 50 milligrams |

Pantothenic Acid | 30 milligrams |

Vitamin D | 1,000 to 4,000 International Units (IU) or depending on confirmed levels |

Other Supplements | |

Probiotics | 109 or 1010 Colony Forming Units(CFU) |

Dietary Fibers: Psyllium husks Resistant Starch |

10 Grams (g) to 25 Grams |

Omega-3 Fatty Acids | 2,000 to 5,000 milligrams |

Laboratory blood test overview

Recommended blood tests for irritable bowel syndrome | |

|---|---|

Normal Values | |

40 to 60 nanograms per milliliter (ng/ml) | |

Omega-3-Index: Average Optimal |

5 to 8 Percent 8 to 11 Percent |

Summary

Irritable bowel syndrome patients suffer from an intestinal flora imbalance. This leads to a wide range of abdominal symptoms, such as pain, a feeling of fullness, constipation, abdominal bloating, or diarrhea.

The cause of irritable bowel syndrome has not been definitively determined. It is suspected that genetic factors are involved. The immune system, nerve disorders, and an intestinal flora imbalance may all play a role.

Micronutrient medicine uses substances which have a positive effect on the intestinal function of irritable bowel syndrome patients. Probiotic bacteria restore a healthy balance in the intestinal flora and so improve the health and activity of the intestinal wall. Dietary fibers improve the effectiveness of probiotics because they provide nutrition to the healthy bacteria. Vitamin D regulates the immune system, as do omega-3 fatty acids, which are able to actively neutralize inflammation. B vitamins enable the intestinal mucous membrane to quickly regenerate.

Study and Source Index

Aller, R. et al. (2004): Effects of a high-fiber diet on symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome: a randomized clinical trial. Nutrition 2004; 20: 735–737. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15325678, retrieved on: 2018-05-08.

Andrews, E.B. et al. (2005): Prevalence and demographics of irritable bowel syndrome: results from a large web-based survey. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2005; 22: 935–942. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16268967, retrieved on: 2018-05-08.

Anti, M. et al. (1998): Water supplementation enhances the effect of high-fiber diet on stool frequency and laxative consumption in adult patients with functional constipation. Hepatogastroenterology 1998; 45: 727–732. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9684123, retrieved on: 2018-05-08.

Barbara, G. et al. (2002): A role for inflammation in irritable bowel syndrome? Gut 2002; 51: 41–44. http://gut.bmj.com/content/51/suppl_1/i41, retrieved on: 2018-05-08.

Bennett, E.J. et al. (1998): Level of chronic life stress predicts clinical outcome in irritable bowel syndrome. Gut 1998; 43: 256–261. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10189854, retrieved on: 2018-05-08.

Bercik, P. et al. (2005): Is irritable bowel syndrome a low-grade inflammatory bowel disease? Gastroenterol Clin North Am 2005; 34:235–245. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15862932, retrieved on: 2018-05-08.

Biesalski, H. K. (2016): Vitamine und Minerale. Georg Thieme Verlag, Stuttgart.

Bijkerk, C.J. et al. (2004): Systematic review: the role of different types of fibre in the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2004; 19: 245–251. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/14984370, retrieved on: 2018-05-08.

Bijkerk, C.J. et al. (2009): Soluble or insoluble fibre in irritable bowel syndrome in primary care? Randomised placebo controlled trial BMJ 2009; 339: https://www.bmj.com/content/339/bmj.b3154, retrieved on: 2018-05-08.

Blanchard, E.B. et al. (2008): The role of stress in symptom exacerbation among IBS patients. J Psychosom Res 2008; 64: 119–128. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18222125, retrieved on: 2018-05-08.

Borsch, J. (2018): Saccharomyces nicht in der Nähe von Schwerkranken. Im Internet: https://www.deutsche-apotheker-zeitung.de/news/artikel/2018/01/22/saccharomyces-nicht-bei-schwerkranken-oder-immunsupprimierten,

Borycka-Kiciak, K. et al. (2017): Butyric acid – a well-known molecule revisited. Prz Gastroenterol. 2017; 12(2): 83–89. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5497138/#sec3title, retrieved on: 2018-05-08.

Chadwick, V.S. et al. (2002): Activation of the mucosal immune system in irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology 2002; 122: 1778–1783. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12055584, retrieved on: 2018-05-08.

Chua, C.S. et al. (2017): Fatty acid components in Asian female patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Medicine (Baltimore). 2017 Dec; 96(49): e9094. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29245334, retrieved on: 2018-05-08.

Clarke, G. et al. (2010): Marked elevations in pro-inflammatory polyunsaturated fatty acid metabolites in females with irritable bowel syndrome. J Lipid Res. 2010 May; 51(5): 1186–1192. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2853445/, retrieved on: 2018-05-08.

Codling, C. et al. (2010): A molecular analysis of fecal and mucosal bacterial communities in irritable bowel syndrome. Dig Dis Sci 2010; 55: 392–397. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19693670, retrieved on: 2018-05-08.

Costantini, L. et al. (2017): Impact of Omega-3 Fatty Acids on the Gut Microbiota. Int J Mol Sci. 2017 Dec 7;1 8(12). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29215589, retrieved on: 2018-05-08.

Dancey, C.P. et al. (1998): The relationship between daily stress and symptoms of irritable bowel: a time-series approach. J Psychosom Res 1998; 44: 537–545. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9623874, retrieved on: 2018-05-08.

Deutsche Gesellschaft für Verdauungs- und Stoffwechselkrankheiten (DGVS) und der Deutsche Gesellschaft für Neurogastroenterologie und Motilität (DGNM) (2011): S3-Leitlinie Reizdarmsyndrom: Definition, Pathophysiologie, Diagnostik und Therapie, AWMF-Registriernummer: 021/016, http://www.awmf.org/uploads/tx_szleitlinien/021-016l_S3_Reizdarmsyndrom_2011-abgelaufen.pdf, retrieved on: 2018-06-12.

Dinan, T.G. et al. (2008): Enhanced cholinergic-mediated increase in the pro-inflammatory cytokine IL-6 in irritable bowel syndrome: role of muscarinic receptors. Am J Gastroenterol 2008; 103: 2570–2576. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18785949, retrieved on: 2018-05-08.

Distrutti, E. et al. (2016): Gut microbiota role in irritable bowel syndrome: New therapeutic strategies. World J Gastroenterol. 2016 Feb 21; 22(7): 2219–2241. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4734998/, retrieved on: 2018-05-08.

Edebol-Carlman, H. et al. (2018): Cognitive behavioral therapy for irritable bowel syndrome: the effects on state and trait anxiety and the autonomic nervous system during induced rectal distensions - An uncontrolled trial. Scand J Pain. 2018 Jan 26;18(1):81-91. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29794287, retrieved on: 2018-06-12.

El-Salhy, M. et al. (2012): The role of diet in the pathogenesis and management of irritable bowel syndrome (Review). Int J Mol Med. 2012 May; 29(5): 723–731. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22366773, retrieved on: 2018-05-08.

Ford, A. et al. (2008): Effects of fibre, antispasmotics, and peppermint oil in the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome: systematic reiiew and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2009; 338: b1881. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3060574/, retrieved on: 2018-05-08.

Fournier, A. et al. (2018): Emotional overactivity in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2018 Jun 1:e13387. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29856118, retrieved on: 2018-06-12.

Foxx-Orenstein, A.E. (2016): New and emerging therapies for the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome: an update for gastroenterologists. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2016 May; 9(3): 354–375. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4830102/, retrieved on: 2018-05-08.

Fuentes‐Zaragoza, E. et al. (2011): Resistant starch as prebiotic: A review. Biosynthesis, Nutrition, Biomedical 2001; 63(7): 406–415. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/star.201000099, retrieved on: 2018-05-08.

Furnari, M. et al. (2015): Optimal management of constipation associated with irritable bowel syndrome. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2015; 11: 691–703. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4425337/, retrieved on: 2018-05-08.

Gröber, U. (2011): Mikronährstoffe. Metabolic Tuning – Prävention – Therapie. 3. Aufl. Wissenschaftliche Verlagsgesellschaft mbH Stuttgart.

Guilarte, M. et al. (2007): Diarrhoea-predominant IBS patients show mast cell activation and hyperplasia in the jejunum. Gut 2007; 56: 203–209. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1856785/, retrieved on: 2018-05-08.

Gwee, K.A. et al. (2003): Increased rectal mucosal expression of interleukin 1beta in recently acquired post-infectious irritable bowel syndrome. Gut 2003; 52: 523–526. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12631663, retrieved on: 2018-05-08.

Hertig, V.L. et al. (2007): Daily stress and gastrointestinal symptoms in women with irritable bowel syndrome. Nurs Res 2007; 56: 399–406. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18004186, retrieved on: 2018-05-08.

Higgins, J.A. und Brown, I.L. (2013)): Resistant starch: a promising dietary agent for the prevention/treatment of inflammatory bowel disease and bowel cancer. Current Opinion in Gastroenterology 29: 190–194. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23385525, retrieved on: 2018-05-08.

Hongisto, S.M. et al. (2006): A combination of fibre-rich rye bread and yoghurt containing Lactobacillus GG improves bowel function in women with self-reported constipation. Eur J Clin Nutr 2006; 60: 319–324. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16251881, retrieved on: 2018-05-08.

Hungin, A.P et al. (2005): Irritable bowel syndrome in the United States: prevalence, symptom patterns and impact. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2005; 21: 1365–1375. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15932367, retrieved on: 2018-05-08.

Jones, M.P. et al. (2006): Coping strategies and interpersonal support in patients with irritable bowel syndrome and inflammatory bowel disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2006; 4: 474–481. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16616353, retrieved on: 2018-05-08.

Kanazawa, M. et al. (2004): Patients and nonconsulters with irritable bowel syndrome reporting a parental history of bowel problems have more impaired psychological distress. Dig Dis Sci 2004; 49: 1046–1053. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1023/B:DDAS.0000034570.52305.10, retrieved on: 2018-05-08.

Kassinen, A. et al. (2007): The fecal microbiota of irritable bowel syndrome patients differs significantly from that of healthy subjects. Gastroenterology 2007; 133: 24–33. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17631127, retrieved on: 2018-05-08.

Kerckhoffs, A.P. et al (2009): Lower Bifidobacteria counts in both duodenal mucosa-associated and fecal microbiota in irritable bowel syndrome patients. World J Gastroenterol 2009; 15: 2887–2892. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19533811, retrieved on: 2018-05-08.

Kindt, S. et al. (2009): Immune dysfunction in patients with functional gastrointestinal disorders. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2009; 21: 389–398. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19126184, retrieved on: 2018-05-08.

Konturek, P.C. & Zopf, Y. (2010): Therapeutische Modulation der Darmmikrobiota beim Reizdarmsyndrom. Von Probiotika bis zur fäkalen Mikrobiota-Therapie. MMW-Fortschritte der Medizin 2017; 159 (S7): 1–5. https://www.springermedizin.de/therapeutische-modulation-der-darmmikrobiota-beim-reizdarmsyndro/15277168,retrieved on: 2018-07-10.

Krogius-Kurikka, L. et al. (2009): Microbial community analysis reveals high level phylogenetic alterations in the overall gastrointestinal microbiota of diarrhoea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome sufferers. BMC Gastroenterol 2009; 9: 95. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20015409, retrieved on: 2018-05-08.

Layer, P. et al. (2011): S3-Leitlinie Reizdarmsyndrom: Definition, Pathophysiologie, Diagnostik und Therapie. Gemeinsame Leitlinie der Deutschen Gesellschaft für Verdauungs-und Stoffwechselkrankheiten (DGVS) und der Deutschen Gesellschaft für Neurogastroenterologie und Motilität (DGNM). Z Gastroenterol 2011; 49: 237–293. https://www.dgvs.de/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/Leitlinie_Reizdarmsyndrom.pdf, retrieved on: 2018-05-08.

Li, Y.C. et al. (2015): Critical Roles of Intestinal Epithelial Vitamin D Receptor Signaling in Controlling Gut Mucosal Inflammation. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2015 Apr; 148: 179–183. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4361385/, retrieved on: 2018-05-08.

Ligaarden, S.C. & Farup, P.G. (2011): Low intake of vitamin B6 is associated with irritable bowel syndrome symptoms. Nutr Res. 2011 May; 31(5): 356–361. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21636013, retrieved on: 2018-05-08.

Lockyer, S. & Nugent, A.P. (2017): Health effects of resistant starch. Biosynthesis, Nutrition, Biomedical 2017: Doi: 10.1111/nbu.12244. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/nbu.12244, retrieved on: 2018-05-08.

Lorente-Cebrián, S. et al. (2015): An update on the role of omega-3 fatty acids on inflammatory and degenerative diseases. J Physiol Biochem. 2015 Jun; 71(2): 341–349. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25752887, retrieved on: 2018-05-08.

Meier, R. (2010): Probiotics in Irritable Bowel Syndrome. Ann Nutr Metab 2010; 57(1): 12–13. https://www.karger.com/Article/Pdf/309017, retrieved on: 2018-05-08.

Menni, C. et al. (2017): Omega-3 fatty acids correlate with gut microbiome diversity and production of N-carbamylglutamate in middle aged and elderly women. Sci Rep. 2017; 7: 11079. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5593975/, retrieved on: 2018-05-08.

Minocha, A. et al. (2006): Prevalence, sociodemography, and quality of life of older versus younger patients with irritable bowel syndrome: a population-based study. Dig Dis Sci 2006; 51: 446–453. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16614950, retrieved on: 2018-05-08.

Murray, C.D. et al. (2004): Effect of acute physical and psychological stress on gut autonomic innervation in irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology 2004; 127: 1695–1703. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15578507, retrieved on: 2018-05-08.

Nwosu, B.U. et al. (2017): Vitamin D status in pediatric irritable bowel syndrome. PloS one 13 Feb 2017, 12(2) :e0172183. http://europepmc.org/abstract/med/28192499, retrieved on: 2018-05-08.

Ohman, L. et al. (2009): T-cell activation in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol 2009; 104: 1205–1212. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19367268, retrieved on: 2018-05-08.

Park, H.J. et al. (2008): Psychological distress and GI symptoms are related to severity of bloating in women with irritable bowel syndrome. Res Nurs Health 2008; 31: 98–107. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18181134, retrieved on: 2018-05-08.

Piche, T. et al. (2009): Impaired intestinal barrier integrity in the colon of patients with irritable bowel syndrome: involvement of soluble mediators. Gut 2009; 58: 196–201. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18824556, retrieved on: 2018-05-08.

Quartero, A.O. et al. (2005): Bulking agents, antispasmodic and antidepressant medication for the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2005; 2: CD003460. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15846668, retrieved on: 2018-05-08.

Rees, G. et al. (2005): Randomised-controlled trial of a fibre supplement on the symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome. J R Soc Promot Health 2005; 125: 30–34. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15712850, retrieved on: 2018-05-08.

Rodin, B.K. et al. (2018): A Review of Microbiota and Irritable Bowel Syndrome: Future in Therapies. Adv Ther (2018) 35: 289–310. https://link.springer.com/content/pdf/10.1007%2Fs12325-018-0673-5.pdf, retrieved on: 2018-05-08.

Rodiño-Janeiro, B.K. et al. (2018): A Review of Microbiota and Irritable Bowel Syndrome: Future in Therapies. Adv Ther. 2018 Mar; 35(3): 289-310. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29498019, retrieved on: 2018-05-08.

Saito, Y.A et al. (2003): The effect of new diagnostic criteria for irritable bowel syndrome on community prevalence estimates. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2003; 15: 687–694. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/14651605, retrieved on: 2018-05-08.

Shulmann, R.J. et al. (2017): Psyllium Fiber Reduces Abdominal Pain in Children with Irritable Bowel Syndrome in a Randomized, Double-Blind Trial. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology 2017; 15(5): 712–719. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1542356516300210, retrieved on: 2018-05-08.

Silk, D.B.A. et al (2009): Clinical trial: the effects of a trans-galactooligosaccharide prebiotic on faecal microbiota and symptoms in irritable bowel syndrome. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2009; 29: 508–18. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19053980, retrieved on: 2018-05-08.

Sinagra, E. et al. (2016): Inflammation in irritable bowel syndrome: Myth or new treatment target? World J Gastroenterol. 2016; 22(7): 2242–2255. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4734999/, retrieved on: 2018-05-08.

Solakivi, T. et al. (2011): Serum fatty acid profile in subjects with irritable bowel syndrome. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2011 Mar; 46(3): 299–303. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21073373, retrieved on: 2018-05-08.

Spetalen, S. et al. (2009): Rectal visceral sensitivity in women with irritable bowel syndrome without psychiatric comorbidity compared with healthy volunteers. Gastroenterol Res Pract 2009: 130684. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19789637, retrieved on: 2018-05-08.

Spiller, R. & Garsed, K. (2009): Infection, inflammation, and the irritable bowel syndrome. Dig Liver Dis 2009; 41: 844–849. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19716778, retrieved on: 2018-05-08.

Spiller, R. & Campbell, E. (2006): Post-infectious irritable bowel syndrome. Curr Opin Gastroenterol 2006; 22: 13–17. https://academic.oup.com/cid/article/46/4/594/298845, retrieved on: 2018-05-08.

Spiller, R.C. (2007): Irritable bowel syndrome: bacteria and inflammation – clinical relevance now. Curr Treat Options Gastroenterol 2007; 10: 312–321. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17761124, retrieved on: 2018-05-08.

Tabas, G. et al. (2004): Paroxetine to treat irritable bowel syndrome not responding to high-fiber diet: a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Am J Gastroenterol 2004; 99: 914–920. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15128360, retrieved on: 2018-05-08.

Tana, C. et al. (2010): Altered profiles of intestinal microbiota and organic acids may be the origin of symptoms in irritable bowel syndrome. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2010; 22: 512–519. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19903265, retrieved on: 2018-05-08.

Tazzyman, S. et al. (2015): Vitamin D associates with improved quality of life in participants with irritable bowel syndrome: outcomes from a pilot trial. BMJ Open Gastroenterology 2015; 2: e000052. http://bmjopengastro.bmj.com/content/2/1/e000052, retrieved on: 2018-05-08.

Williams, C.E. et al. (2018): Vitamin D status in irritable bowel syndrome and the impact of supplementation on symptoms: what do we know and what do we need to know? Eur J Clin Nutr. 2018 Jan 25. doi: 10.1038/s41430-017-0064-z. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29367731, retrieved on: 2018-05-08.

Załęski, A. et al. (2013): Butyric acid in irritable bowel syndrome. Prz Gastroenterol. 2013; 8(6): 350–353. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4027835/, retrieved on: 2018-05-08.

Zhou, Z. et al. (2013): Effect of resistant starch structure on short‐chain fatty acids production by human gut microbiota fermentation in vitro. Biosynthesis, Nutrition, Biomedical 2013; 65(5–6): 509–516. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/star.201200166, retrieved on: 2018-05-08.